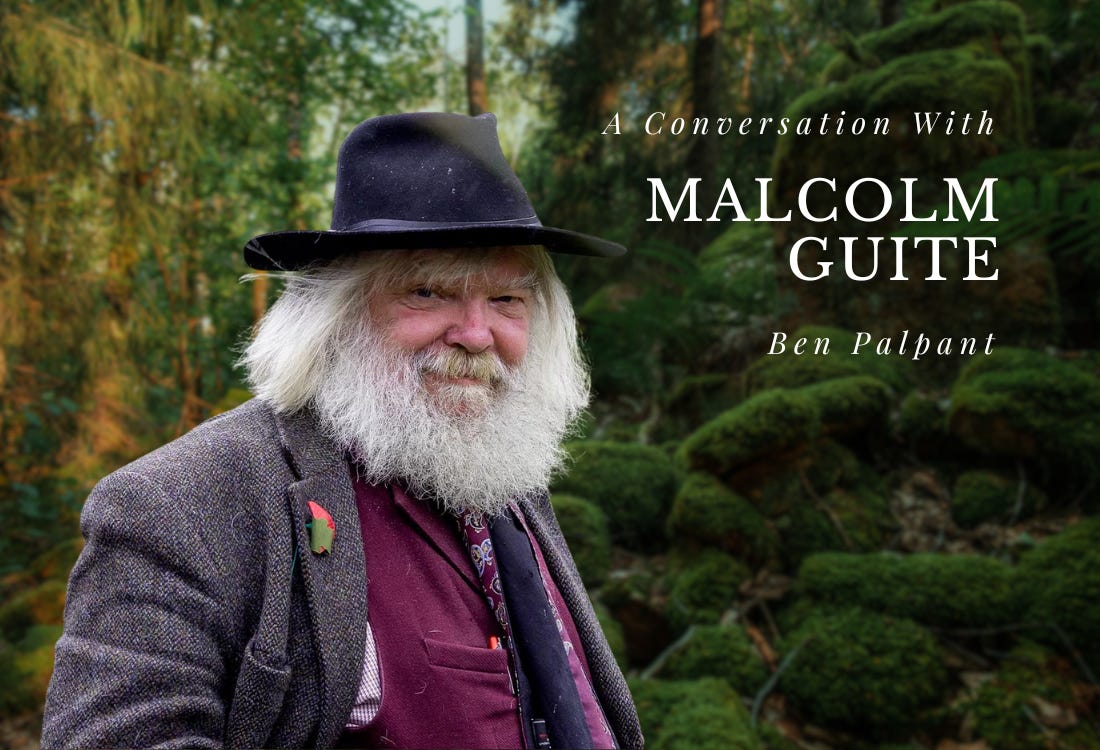

A Conversation With Malcolm Guite—Ben Palpant

An Interview by Ben Palpant | Words Under the Words No. 9

This post belongs to a series of interviews between Ben Palpant and important contemporary poets.

For more articles, videos, books, and resources about faith and art, visit RabbitRoom.com.

Begin the song exactly where you are. Remain within the world of which you're made. Call nothing common in the earth or air. Accept it all and let it be for good. Start with the very breath you breathe in now, This moment's pulse, this rhythm in your blood And listen to it, ringing soft and low. Stay with the music, words will come in time.

—from "The Singing Bowl" by Malcolm Guite

Many years ago, my daughter went through a difficult season. Walking with a child through the valley of the shadow of death is a daunting journey that accentuates our dependence on God; at least, it did so for me. Feeling my limitations rather acutely one day, I decided to take her on an overnight camping trip to the St. Joe River. I had two modest goals for the trip: first, to enjoy the mountain air and what Wendell Berry called "the peace of wild things" and, second, to memorize Malcolm Guite's "Singing Bowl."

That’s why, to begin our conversation, I thank Malcolm for the poem and for giving me the words I needed when I needed them, words that could minister to my daughter when my own words had run their course.

While he lights his pipe, he says, "Well, you know, at the time I wrote that poem, I thought I was writing a poem about how to write poetry, but it turned out to be a poem about prayer and living a life open to God. It was a bit of a revelation to me because I was feeling a bit of a tug between my vocation as a priest and my vocation as a poet. I was wondering if I was sort of robbing Peter to pay Paul. One of the effects of that poem was to help me realize that, no, these are really two sides of the same coin."

"What is your most popular poem?"

"Well, let's see. It's probably 'My Poetry Is Jamming Your Machine.'

Of course, if I'm measuring strictly on grateful correspondence, I get quite a bit of response for a couple of poems I wrote about darkness, difficulty, and depression. The first one is 'The Third Fall' and the other is 'The Christian Plummet.' People from all walks of life share how the poem touched them in particular ways that surprise me, you know. One of the things about poetry is that it's always about more than you think it's about. That's almost my definition of a poem. I usually have some idea of what I'm going to write about, but if I write it down and it turns out to be exactly what I set out to write about and nothing more, then I don't think it's a poem, it's a note to self. It has to quicken itself in the making and push back against me a little and take some sort of living form. It has to resist me a bit in order for me to know that it's a poem."

"You bring up depression. Many of your poems are helpful companions during dark times. When your poems touch on difficulty, they do so as one who has experienced it and yet you're such a jolly man. How is that?"

"Ah, yes, well, a couple of things about that." He laughs. "As you know, these are things we all share in common. One of the things I consciously resist and rebel against is the idea of poetry as just personal self-expression. The idea of the lonely, romantic genius in his weird, peculiar place, who everyone has to make allowances for leads to this kind of confessional poetry which gets worse and worse and more and more obscure. What does it amount to? Another strange adventure in the little world of me. I don't buy that at all. No, I want to be the bard of a tribe, to tell the great, collective stories that bind us together, but, of course, I tell them as they've happened to me. Whatever is personal of mine, is most emphatically not in the poems as purely self-expression. Confessional poetry becomes very tedious after a while. The poetry I want to write and that I enjoy reading articulates the joys and sorrows of life. As to the jollity, I suppose I would say that anyone with lighter emotions who hasn't experienced any pain is in danger of sentiment. I trust them about as much as I trust a Thomas Kincaid painting. You know, there's a term Tolkien coined, eucatastrophe. Eu, meaning good, so a good catastrophe, but it still has the word catastrophe in it. In some sense, the eucatastrophe at the end of the Lord of the Rings is trustworthy because we've been with these characters to the very edge of the crack of doom. That's why I trust the resurrection because the church doesn't backpedal on Good Friday."

"While we're on the topic, who calls depression 'the black dog'? Is that Churchill?"

"Churchill used it, but it comes from Samuel Johnson who was, as you know, a great Christian, but he had terrible periods of darkness. He was doggedly latched onto Christianity, though. It's a very helpful metaphor, the black dog, because a dog is both a domestic thing as well as a potentially dangerous thing. In my own life, there have been times when it was quite severe."

"I'm glad I'm not alone."

"Here's something interesting. I've always been an enthusiast for boats, for sailing. I remember ardently reading a book about cruising around on small boats and the chapter on sea sickness. It had pages upon pages of apparently useful information, at the end of which it said most of this would probably not work, but the last words of the chapter were, 'In the end, the best you can do is keep your face into the wind and endeavor to remember that it can't last forever.' I thought that was brilliant and I've applied it to the black dog of depression. I particularly like the phrase 'endeavor to remember' because, obviously, when you are actually feeling seasick, you cannot imagine anything except nausea. It's a totalizing experience, but you can endeavor to remember. You can try to want to remember. One of the best cures for my dark seasons is turning my face to the wind. Someone once asked me what floats my boat and I said, well, it's quite literally floating on a boat."

"Endeavoring to hope means, I suppose, learning to hope."

"Yes, well, you know, hope is a kind of gift of the Spirit. Hope has one foot in heaven already. It's about the in-breaking of heaven into time. It's not about believing that nothing bad is ever going to happen."

"Your comments have brought something to mind. This question might seem out of the blue, but I promise I'm going somewhere with it. Is Malcolm actually your first name?"

"Ah, I see where you're going with this. Yes, Malcolm is actually my middle name. My first name is Ayodeji (eye-oh-day-jee). It's a tribal name from Nigeria. Ayo means joy and deji means again, so a double joy. I was born in Nigeria in 1957, but I was very nearly not born. Due to some complications at my birth, things came to a kind of crisis. I was getting strangled by my umbilical cord. It was nearly the end for my mother and for me, before I had even seen the light of day. Anyway, there was only one person who was able to make the necessary interventions and he was just leaving the compound in his car. A nurse ran out and stopped him and he performed a fairly swift cesarean section, which saved both my mother and me. My mother, being obviously very grateful to the nurse, asked her what to name me and the nurse said Ayodeji because it is a traditional name for a second child—which I am—and because it was very nearly sorrow rather than joy, but joy was granted, which makes it a double joy."

"That's an incredible story."

"Yes, it is. Chesterton's father pointed to a man who had shown great promise in life but who was a failure in the end, and said, 'That man is a great might have been.' Chesterton resists this phrase. He says, 'No, everything hangs by so thin a thread, every one of us is a great might not have been.’ The fact that we exist at all is a cause for great rejoicing. It's so helpful to think of one's life as an unexpected bonus rather than a deserved certainty."

"That perspective would change how we enter each day. I'm amazed that you have so thoroughly lived into your name's meaning. That probably happens to people a lot more than we realize. Do you agree?"

"Yes, absolutely. You know, my middle name, Malcolm, has become more and more significant to me. It was chosen by my grandmother. The first meaning of my name means I'm a disciple of Saint Columba who evangelized Scotland, which, in terms of Celtic Christianity, suits me just fine. But its deeper meaning is that I'm a servant of the Spirit. That leaves us with my last name which is rather inexplicable. My father's family came over, probably from the south of France, with the Huguenots after the Edict of Nantes. I can find no meaning for it except for a Provencal dialect word that means madman. So I think that fits fairly well."

We’re both laughing so hard that it takes me a moment to collect my wits. Finally, I say, "In One Long River of Song, Brian Doyle writes, 'I walked out so full of hope, I'm sure I spilled some at the door.' Your mother couldn't have known that that was the little boy she was bringing into the world, but it seems to me that it's what you continually do."

"Well, everything comes and goes, but I am, essentially, hopeful. I think it's a better word than optimistic because of, you know, the great saying of Jesus from the cross, 'It is finished.' A corner has been turned. Darkness has been defeated. Because people like a rehearsed testimony, they ask if I know on what day I was saved and I say, yes, it was Good Friday, same as you."

"Amen, brother."

"I think we're entitled to joy—a real joy, not a naive optimism. Vaclav Havel says somewhere that hope is not the certainty that things will turn out well, but that they will make sense, that they will mean something."

"I think it was Chesterton who said a stone will, by its own nature, fall because hardness is weakness. A bird, however, will, of its nature, fly because fragility is force."

"Yes, yes! That's where he goes on to say that angels can fly because they take themselves lightly. He got that, of course, from George MacDonald who wrote The Light Princess."

"Okay, I'm going to yank the steering wheel and veer off of this road and onto a new one."

"Yes, fine, fine."

"What's your take on the fact that the reincarnation of Bilbo Baggins—if I may call you that—has nearly 100,000 followers on YouTube?"

He laughs and ruffles his hair. "I'm just being me. There's nothing more than that. It began, more or less, during the first couple of days of the Coronavirus lockdown. I was still engaged as chaplain as well as a teacher at Cambridge, but I was stuck in my little village and my students were stuck wherever they were and none of us could meet. My entire mode of being chaplain was about presence and about being glad to welcome people. In so far as I had a spiritual discipline, it was a ministry of presence. My golden rule, the thing I prayed to be given, was to be glad to be interrupted. Whatever I was doing when someone knocked on my door, even if I was right in the middle of a particularly delicate sentence, I would remind myself that this is a good thing and I would say, 'come, come in.' That's how I start every video. So that little video thing was my way of pretending that we could still meet, you see. It was meant only for my students and a handful of friends. I suppose I've become a bit of what they call an influencer, but I would have been voted boy most unlikely to become one." He laughs. "I find it amusing that people who take YouTube seriously, who work really hard at it and have fewer followers are writing to ask about my strategies, about all this technical stuff—lighting, schedule, staging, and all the rest—God help us all! People, there is no strategy."

"So why the following?"

"I think that social media and YouTube have become such contested, nauseous, and poisonous places that what I offered was something that a very large number of people needed which was this quiet little haven and a feeling that some sense of truth, beauty, and simplicity has been restored to them. Honestly, my hope is that my videos will help people stop watching YouTube altogether and go read a book. That's the whole game of it. What we're happily accepting is the illusion that there are no flat screens involved in this encounter at all."

"And you're just delighting in what you enjoy; namely, good books. It's nothing but hospitality and boyish enthusiasm."

"Yes, exactly."

"When I spoke to the poet, James Matthew Wilson, he described a crisis he faced during his post-grad work. The very thing that drew him to study the humanities—the love of good writing and of good stories—was replaced by deconstruction and politics."

"It's really true. I'm glad I got out of academia before all of that really took off. It won't last. I mean, theory tends to eat itself in the end. All of the structuralism, post-structuralism, and critical deconstruction has already begun to deconstruct itself. People have started returning to reading with the grain of the text rather than against the grain."

"That's what you're doing on your YouTube channel and it's refreshing."

"I hope so."

"Coleridge has been a major influence on your life. How did you two meet?"

"Coleridge is huge. You know, if you read at all widely, you're bound to find writers who feel like kindred spirits with whom you resonate. Coleridge is very much that for me. I empathize with him enormously. I met his poetry before I met him because my mother had a huge fund of poetry memorized by heart from which she would pull as the occasion arose. When I was a kid, we spent a great deal of time traveling by sea, you know. Returning to England from Nigeria every year took quite a long time back in those days. It was always quite a moment when the ship would leave the harbor and we would watch the furrow and the wake of the boat. And she would quote 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,' saying, 'we were the first to burst into that silent sea.' And, of course, I would like to hear more. So I knew that poem quite well. I started diving into his work more seriously later in high school, reading his prose and so on. I found him to be a very interesting figure.

"Then, when I, myself, began to make the intellectual and imaginative journey back into Christianity, having rejected it in my teens, I had this memory that Coleridge had quite a bit to say about this. So I went back to him and found that he had written this wonderful, mature, and philosophically deeply grounded return to a fully Trinitarian faith. I looked, again, at the textbooks we've been given about Coleridge and there's nothing at all about that. They just portray him as this romantic ruin, as it were. There's a lot about opium, but almost nothing about God. Secular historians tend to airbrush out what they're not interested in, to see religious faith as a kind of background noise to action. So I resolved that, one day, I would write an account of Coleridge that restored the full picture. That book became Mariner in which I set out to make a case for his relevance now, our need for him in the cultural crisis we enter today. I found in him a companion, especially when it came to his view of the imagination as a truth-bearing faculty."

"Coleridge has been more than a companion to you, he has strengthened your foundations and informed your thoughts."

"Yes, and now I find him at my side again. One of my childhood dreams was to write an Arthuriad, to do a new setting out of the matter of Britain, as it's called. I was searching for the poetic form and found it in the ballad form, which Coleridge remade, making it capable of carrying great weight. He kept all of the ballad form’s lucidity and readability, but he also allowed it to become a vehicle for something beautiful and luminous and permanent. I'm not saying that I'm going to achieve that, you know, but at least I can try."

"How ambitious is this project?"

"If I live long enough to complete the whole thing, it will be four volumes, each volume consisting of three books so that it becomes a proper twelve-book epic."

"So something modest in length, as in the tradition of Virgil and Milton?"

He laughs. "The whole idea is a little outrageous, I know. It's not, as Swift would say, a modest proposal, but, you know, I'm working on it."

"I love it. You've given yourself a project that gets you up in the morning with an eager step."

"Absolutely. The imagination is like any other faculty, you have to exercise it. I'm daunted by the project, of course, but I'm also excited by it. I don't know which day will be my last, but I can only do the work in front of me."

"Do you ever feel the fear that Keats felt? Doesn't he say, 'when I have fears that I may cease to be...'"

"Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain.' Yes! Great poem, that. But I also believe I'm in the hands of God. As someone says in Narnia, we're always between the lion's paws, you know. In the end, I just hope that whatever God allows me to complete will be of some good in the world. I want to write something that satisfies every age. As George MacDonald said, he wanted to write fairy tales for everyone who loves them, from five to fifty-five. I don't want to simply preach to the choir, as it were. What I really want is for some future C.S. Lewis who is a brooding atheist teenager, to pick up my Arthur poems and love them just for themselves. And then for him to find that they have given him something with which or through which to discover the truth in Christianity. I want my poems to have snuck past the watchful dragons of our secularism and the immanent frame and actually open something up inside him."

"That's a wonderfully rare vision for one's work. It's so wonderful to imagine that you made me forget my question."

After laughing, he says, "I apologize."

"Well, thinking about C.S. Lewis as a brooding teenager reminds me that he said his imagination was baptized. An interesting way of looking at it. George MacDonald's work did the heavy lifting, of course, but it was his walks with Tolkien that helped as well."

"Indeed."

"We bought some acreage a few years ago that we hope to build on someday. The first thing we did was cut a footpath which we called Addison's Walk, based on the path that Lewis and Tolkien walked in Oxford. People often ask, ‘Who is Addison?’, so we get to tell them the story."

"Very good. And, of course, they ought to ask, ‘Who is Addison?’ He wrote a brilliant essay in the early 1700's, on gratitude and on the need to restore the sense of gratitude. In the course of that essay, he presents a poem that has become a great hymn of the Christian church. It begins like this: 'When all thy mercies, O my God, my rising soul surveys, transported with the view, I'm lost in wonder, love, and praise.' Now that wouldn't be a bad verse to put up on your Addison's Walk."

"Not bad at all. That's a great idea. It's a fitting verse for your work, too."

"Well, you know, Maggie and I chose that as the opening hymn to our wedding and I timed it so that when I turned to see the bride, I was singing with everyone else, 'transported by the view, I'm lost in wonder, love, and praise.'"

"That's absolutely wonderful. How long have you two been married?"

"We're going on forty years of marriage."

"What a gift."

"Yes, she has been a gift. You know, she kind of holds the kite strings."

"Maybe we could close this conversation with a poem from your book Sounding The Seasons. One of the things I love about your poetry is the sense of a blessing that comes at the close of the poem. Many of your poems resolve in a kind of grace at the end. I was hoping you would read 'Jesus Weeps' and talk about it a little bit before I leave you alone because I think it's fitting for our time; which is to say, I think it's fitting for any time."

"I'd be happy to read it."

Jesus comes near and he beholds the city And looks on us with tears in his eyes, And wells of mercy, streams of love and pity Flow from the fountain whence all things arise. He loved us into life and longs to gather And meet with his beloved face to face How often has he called, a careful mother, And wept for our refusals of his grace, Wept for a world that, weary with its weeping, Benumbed and stumbling, turns the other way, Fatigued compassion is already sleeping Whilst her worst nightmares stalk the light of day. But we might waken yet, and face those fears, If we could see ourselves through Jesus’ tears.

"I guess there's sort of two ideas that I was playing with in that poem. I want to challenge the idea that people are blinded by tears. Maybe, since tears are a sign of love, maybe they actually clarify our vision. To know that you've been wept for is to know that you've been loved. The other thing I was trying to wake us up from was compassion fatigue. Is that a phrase used in America?"

"Yes. It's a very real concern, especially in the medical field."

"I played with the idea that if compassion fatigue—already so weary—falls asleep, then we're in a really bad spot, totally incapable of response while our worst nightmares parade around. So what is the solution to the problem of compassion fatigue? It seems to me that if we weep with Jesus, that if we see ourselves through his tears, but we also see the world through his tears, then we start seeing people through the compassion of Jesus. We might waken yet, you know. Jesus renews in us the capacity for compassion, but also the capacity for tears. I think about the great phrase in Virgil's Aeneid, when he says lacrimae rerum, the very tears of things. The fallen world itself is worthy of tears and an elegy. I mean, if the answer to that cliche question, 'what would Jesus do?' is to cry, then cry."

"And, as you so often remind us, if Jesus were to laugh in a given moment, then we should laugh as well."

"Yes, indeed."

Ben Palpant is a memoirist, poet, novelist, and non-fiction writer. He is the author of several books, including A Small Cup of Light, Sojourner Songs, and The Stranger. He writes under the inspiration of five star-lit children and two dogs. He and his wife live in the Pacific Northwest.

Malcolm Guite is an English poet, singer-songwriter, academic, and Anglican priest. Guite earned degrees from Cambridge and Durham Universities. He is a Life Fellow of Girton College, Cambridge. He is the author of five books of poetry as well as several books on Christian faith and theology. You can join his community of nearly 100,000 on YouTube.