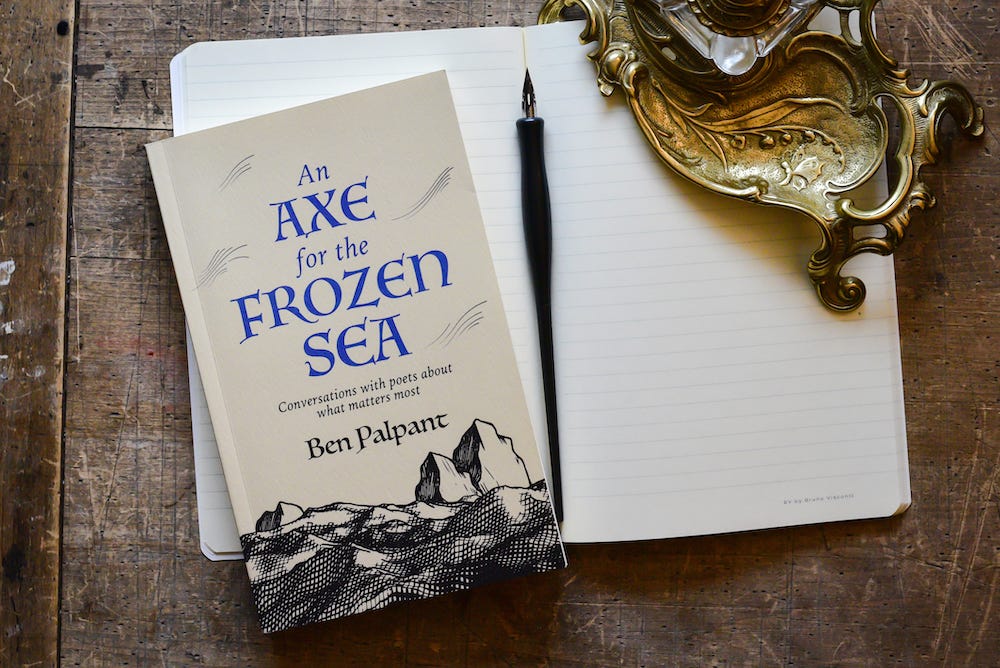

Announcing: An Axe For The Frozen Sea—A New Book From Rabbit Room Press

"Conversations with poets about what matters most."

Editor’s Note: A year ago, when we invited Ben to interview “a few poets” for the Rabbit Room poetry Substack, I never thought it might grow into a book in its own right. Now, after seventeen interviews and a lot of behind-the-scenes work, Rabbit Room Press is proud to announce the release of An Axe For the Frozen Sea.

“Axe” is a remarkable collection of candid interviews with some of the most important poets of faith of the 21st century. Below, you’ll find Ben’s reflection on the process of putting this book together—and the insights he gained along the way.

Order your own copy of “Axe” and read these interviews again and again.

by Ben Palpant

If you had told me, back when I was just a lad, that I would choose to spend much of my 40s in conversation with poets and, worse yet, writing poems myself, I would have kicked you in the shins and run for the hills. I don’t think my boy-sized brain could have conceived of a worse insult. Then, I met a living poet. It happened this way:

I was a senior in high school, holding a paper plate in a potluck line next to a stranger. Because my mother taught me to be polite, I struck up a conversation.

“What do you do?” I asked.

“I’m a poet,” he replied.

I thought he was pulling my leg, but his face said otherwise. No smirk. No glint in his eye. I thought every last poet was dead, pinned onto the pages of boring textbooks, but here was a living one standing next to me, speaking to me in my native tongue. I fled.

You see, when I was in high school, poems struck me as random acts or, maybe worse, a riddle. They made me miserable. Even the poems written in form felt like riddles, which were fun to untangle for those who liked riddles, but they still weren’t very inviting. It seemed to me that poets were writing something out of reach just show they could do it. I wasn’t even sure they knew what they were talking about.

Then, years later, I faced a health crisis that radically impacted my cognition for an extended period of time. Calamity tends to open our hearts to poetry. During that season of my life, I could not track an argument in prose, but I could follow a line of poetry to where it disappeared in the grass. It became important to my physical and mental stability that I learn to stand still in my heart, to wait patiently until my mind could pick up where the next poetic line offered itself and follow it. In poetry, I found unexpected comfort and, strangely, clarity—at least, a kind of clarity, the kind that poetry offers in paradox and metaphor. Poetry offered me insights that drew me deeper into life, and, in particular, my life with Christ. Poetry drew me, as Aslan says in The Last Battle, “further up and further in.”

All these years later, poetry has come to play a significant part in my walk with God, which is why I set out at the start of 2024 to meet as many poets as I could and to spend an hour with each one—not to pepper them with questions, but to have a conversation that would lead us both further up and further in.

You might be asking, “Why interview poets?” To which I answer that I believe the best poets practice seeing what most of us overlook or take for granted. They know how to honor the particularities of human existence, thereby opening our eyes to see ourselves, God, and all of His creation with greater clarity and appreciation—an appreciation that leads from praise to greater praise. Poets draw us to attention. They help us sit up and take note, leading us to the heart of things and beyond the heart of things.

In other words, I believe poets can help us become more human—as God intended. Poets, through the ordinary means of the written word, can give us glimpses of the eternal. That’s why I wanted these interviews to be less about the questions and answers and more about the human interaction. I wanted them to read like two people trying to dig deeper into what it means to be human, two friends exploring why poetry matters for all of life.

In a recent article, Abram Van Engen mentioned that the word ‘stanza’ comes from the Italian for ‘little room.’ Which means that each stanza, at its best, plays host to the reader, welcoming us into not merely an idea or a statement but a place where we are changed. Poets create little rooms, decorating and furnishing them as an act of hospitality. They create rooms, dwelling places, for readers to enter and commune with the poet. As Karen An-hwei Lee put it, “Poetry is a shared experience, even a form of communion, insofar as it is an exchange of intimate thoughts or emotions.”

I did not intend to collect these conversations into a book, but it became apparent rather early on that reading them next to each other would be a reinforcing and fulfilling experience. Each interview is interesting and fruitful, but together they would strengthen and enrich one another. So we decided to compile them into a book—a conversational gift, really—that would allow poets to meet us where we are as fellow pilgrims. Its title, An Axe For The Frozen Sea, comes from my conversation with Mischa Willett who mentioned Franz Kafka’s famous line, “A book must be an axe for the frozen sea within us.” That line stuck with me, and so I decided to title the book what I hope it will become. Starting with the sea that threatens to freeze inside me from time to time.

Over the years, poetry has helped break up the sea of ice in my heart, which makes poets, I suppose, axe-wielders. I don’t mean to describe these poets as people who have weaponized their words—though some of them might embrace that description—I mean that they have chosen the more difficult work of changing hearts. Heart change always begins with the poet, of course, but out of change of heart, the mouth speaks.

You will quickly discover that the poets in An Axe For The Frozen Sea do not always agree. Their convictions vary, as do their practices. One of the interesting convictions they share, however, is that poetry is more than mere self-expression. In my conversation with Malcolm Guite, he put it this way: “One of the things I consciously resist and rebel against is the idea of poetry as just personal self-expression. The idea of the lonely romantic genius in his weird, peculiar place whom everyone has to make allowances for leads to this kind of confessional poetry which gets worse and worse and more and more obscure. What does it amount to? Another strange adventure in the little world of me. I don’t buy that at all.”

Well, if it is not merely self-expression, then what is it? I encourage you to read the book and find out. What you discover will, I think, bless you deeply because it comes from people like you and like me. Like us, they worry, they hope, they forget, they remember. Like us, they long for a richer experience of life. Entering into a relationship with them has enriched my life and I hope it will enrich yours.

I will be asked why I included some poets and did not include others. How I wish I could say that I picked these poets for particular reasons. Alas, I can’t. I started with four poets who lived within driving distance. They, in turn, suggested other poets and so the project evolved organically. These poets by no means represent an exhaustive list of anything. Some are more famous than others, but fame is no indicator of quality and only time will tell which poets will have a lasting impact. At the end of the day, the world is full of worthy poets. Find them. Learn from them.

Given a thousand possible ways to structure An Axe For The Frozen Sea, I opted to organize the poets alphabetically. It allows them to speak to each other and to us without any orchestration on my part. I also have a Get Out Of Jail Free card which I find entirely convenient if anyone complains about the order.

Many years ago, a young woman asked me, “What is poetry for?” It’s a common question, a question that presupposes a practical end. It starts by assuming everything has to be good for something, that a piece of art can’t just exist for the sake of existing, for the sake of adding something beautiful to the world. Beauty doesn’t bow to pragmatism. Rather unfairly, I dodged the question with my own question: “What are the psalms for?” My question made her realize that there isn’t a quick answer. The psalms are too complex and too beautiful. They are so meaningful, they resist reduction. The psalmist gives us words to explore the full gamut of human experience in language that reflect the surging in the human heart. The psalmist gives us language to talk to ourselves and to God. We find comfort and encouragement in the psalms, but those come from relating to the psalmist, not necessarily from getting more information.

In my conversation with the poet, Robert Cording, he said that “poetry is always trying to see beyond what we can see. We know that’s impossible and yet we can, as Scripture says, see through a glass darkly. We know more than we can say.” Or, as Scott Cairns put it, “I really do feel that when I’m making a poem, it’s not about having a glimpse of something true and then trying to transcribe it. It’s more like trying to figure it out, glimpsing it as I go, wrestling with the language, listening to the music of the words, letting the music lead me to the next words.”

Cording and Cairns are not alone. The poets I spoke to all agree with Eliot’s famous line about writing poetry: “every attempt is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure . . . And so each venture / is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate.”

The question asked by every undergraduate, “Is poetry still relevant?” is a worthy one. The answer these conversations give is a resounding, “Yes!” But how is poetry relevant? Well, the answer to that question is as varied as the poets themselves.

When I look over the broad landscape of society, I see a reawakening of interest in and writing of poetry. If I’m correct, we need the best poets—both the living and the dead—to guide us into a deeper relationship with God, with ourselves, and with the world. Li-Young Lee once said, “People who read poetry have heard about the burning bush, but when you write poetry, you sit inside the burning bush.” We need poets whose souls are fully awake so that we might glimpse what they sense throbbing at the heart of all things.

As the story goes, St. Augustine, weary of writing one day, decided to get some fresh air and walk the beach. He had not walked far when he saw a boy dashing back-and-forth from the ocean to a tiny hole in the sand. Augustine called out, “Hey there, what are you doing?”The boy lifted a shell which he had been using to transport sea water and cried out, “I’m going to fit the entire sea into this tiny hole I have dug in the sand!” Augustine laughed aloud. Spreading his arms wide, he said, “You attempt the impossible, my son. You will never fit this magnificent sea into that little hole.” The boy, apparently familiar with the great theologian’s efforts, called back, “And you will never fit the Holy Trinity inside your head!”

Well, imagine that there were two boys instead of only one, or a boy and a girl. Would their success rate improve? Hardly, but it would be good sport to watch. I suppose that’s what these conversations amount to in the end. It’s just two people trying to spoon the ocean into a tiny hole for an hour or so, doing our darndest not to spill a single drop along the way.

If you are a poet, An Axe For The Frozen Sea is for you. May it inspire, instruct, and strengthen you for the work God has given you to do. If you are not a poet, may it remind you that words matter, that poetry matters, and that you matter—not in that particular order. Most of all, may these conversations spur us on to call out to God who loves to answer, so that He will show us great and mighty things which we did not know ( Jeremiah 33:3).

You are a beautiful soul and this is a great essay but you have forgotten to tell us the most important thing— where can we order the book?

What a wonderful, luminous article. Incredibly excited for this