If you want to hear more from Karen Swallow Prior, read her Substack, The Priory, or catch her keynote address at this year’s Housemoot conference, the Rabbit Room’s in-home web conference.

Starting my own Substack was largely a way for me to regain a semblance of the classroom teaching experience I lost last year. In light of that, I hope you’ll indulge me if I propose some structure in how we approach our topic in this post, John Donne’s classic poem “Death, Be Not Proud.”

If we were in an actual classroom together, I would first pull up a clip from Wit, the film adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize-winning play written by Margaret Edson. We would dim the lights and watch this five-minute clip together. (Since we are setting the scene properly here, I should mention that I would fumble with the controls a bit until some kind student feeling sorry for me would come and get it going for me just before I call for IT to come to the rescue.)

Now the clip is up and it’s ready to play. So please, class, stop reading and watch this. It makes an excellent introduction to the poem (and to metaphysical poetry more generally).

I could teach a whole class about this film. I won’t do that here, but may I point out a few brilliant lines? They are all lines spoken by Dr. Evelyn Ashford to Donne-professor-now-cancer-patient Vivian Bearing, who remembers their exchange years later as she faces her own impending death.

“Begin with the text, Miss Bearing, not with a feeling… This is metaphysical poetry, not the modern novel… If you go in for this sort of thing, l suggest you take up Shakespeare.”

“Nothing but a breath, a comma... separates life from life everlasting… Life, death, soul, God... past, present. Not insuperable barriers. Not semicolons. Just a comma.”

These lines alone—and the entire film—demonstrate what can be gained and understood by reading good poetry well.

And in Donne, we have some of the best poetry ever written. To wit, “Death, Be Not Proud”:

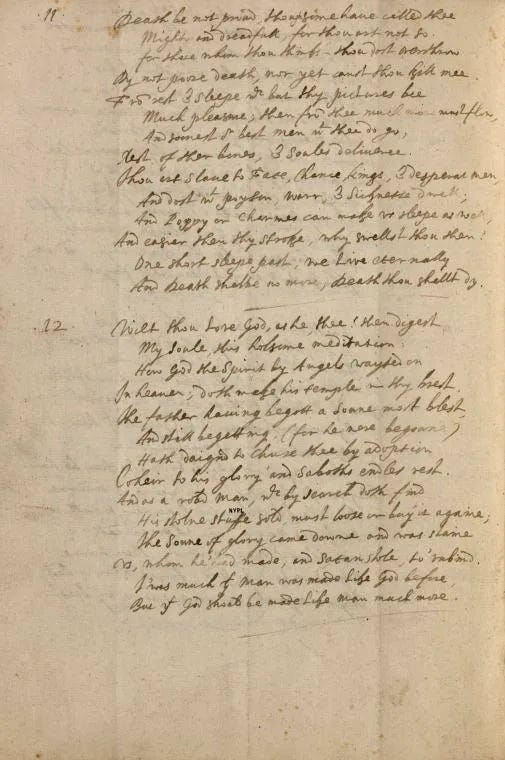

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery. Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

(Ironically, given the conversation in the video clip, my go-to source for these poems uses the semicolon. Discussions of which manuscripts and editions are most correct and authoritative are questions not for this occasion!)

Also related to the punctuation, there is actually quite a bit of debate about the best way to read the poem and how many and which of its metrical feet are iambic. Some of that is lost in translation from 17th-century British English to 21st-century American English. Here is one of the better readings of the poem that I found.

This is one of those sonnets by Donne that combines the Italian and English forms. Like the traditional Italian form, its larger structure consists of an octet and sestet. Yet the rhyme scheme ends with a couplet as Shakespeare’s English sonnets did. (Note that “eternally” and “die” form an approximate rhyme—which counts as rhyme.)

An emphasis in thought occurs at the beginning of the sestet and another at the beginning of the closing couplet. On the other hand, these are really culminations of the poem’s entire argument rather than turns in thought: Death, you have no cause to be proud.

The poem takes the form of an apostrophe: an address to someone (or something) absent. In addressing death this way, death is also personified, not only through apostrophe, but also throughout the poem through the imagery that describes death as a usurper, as a thief, as one who dwells with ne’er-do-wells, and as a finite, living being destined to die—and die forever, unlike those he thinks to kill.

So much of the poem’s effect is found in the sound: the usual rhythm of iambic pentameter and the sounds of the letters themselves, with much repetition within and between the lines.

With almost no overly difficult vocabulary in this poem, it’s one I encourage you to read aloud for yourself several times. Try different emphases to hear which one conveys the meaning best. Listen to how the harsh consonants and the long vowel sounds contribute to the firmness and confidence of the poem’s dismissal of death’s power.

In addition to sound, the poem relies heavily on irony and paradox, which reach their peak in the last line with the declaration that death will die.

Before that, we are presented with several other ironies:

If sleep is a “picture” or image of death (a common trope in poetry of this time, as well as in Shakespeare), and if sleep brings us rest and the pleasure of dreams, then how much more pleasure will the real thing (death) bring us?

When death takes the “best men” (perhaps brave warriors or other noble men), death brings rest to their bones and delivery of their souls.

Death is the “slave” to those things that cause death: fate, chance, the rule of law (kings), and criminals (desperate men).

Death (so haughty and proud) is but the companion of poison, war, and sickness.

Drugs and magic spells can also make us sleep as well as death—better, actually!

Death is but a sleeping that allows us to awake in eternity.

This leads us to the greater point that death dies when we enter eternal life. Death ushers us into eternity. Dr. Ashford in Wit explains it best—with a breath. A mere comma.

You would be right to hear an echo in the poem of 1 Corinthians 15:55: “O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?” (KJV)

Death, be not proud indeed. Christ is victorious over death.

You don’t have to be a Christian to agree that death is one of—if not the—thing most wrong with this world. There are other reasons for my faith in Jesus. But the greatest one is that he overcame death—not just his own, but all death. In my book, such a God is worth believing in.

Originally published on Karen Swallow Prior’s Substack, The Priory.

Karen Swallow Prior, Ph. D., is a reader, writer, and professor. She is the author of The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images, and Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis (Brazos, 2023); On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books (Brazos 2018); and several other books. Her writing has appeared at Christianity Today, New York Times, The Atlantic, The Washington Post, First Things, Vox, Think Christian, The Gospel Coalition, and various other places. She hosted the podcast Jane and Jesus.

I wonder … is that the first use of Arvo Part’s “Spiegel im Spiegel” in a film or tV episode?

I know that’s not the point of this essay AT ALL, but now, when I hear the song or read the sonnet, it will be the sound of that comma.

This was the balm I needed today. Oddly enough, Donne always soothes my spirit. Thank you for sharing.